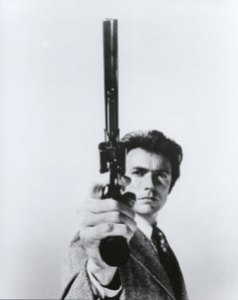

Clint Eastwood, like John Wayne, embodied the American icon. From the mysterious cowboys to the gun-toting Dirty Harry, many of his characters embodied traits that Americans readily identify: loners, anti-establishment, rebels, smart, pragmatic and intentional or unintentional redeemers of the downcast. In his recent, Gran Torino, Eastwood plays yet another loner, Walt Kowalski.

Clint Eastwood, like John Wayne, embodied the American icon. From the mysterious cowboys to the gun-toting Dirty Harry, many of his characters embodied traits that Americans readily identify: loners, anti-establishment, rebels, smart, pragmatic and intentional or unintentional redeemers of the downcast. In his recent, Gran Torino, Eastwood plays yet another loner, Walt Kowalski.

At the beginning of the film, his wife just died and he obviously has no relation with his children. Mr. Kowalski, as he prefers to be called, relates better to his dog than to other humans. He lives in a neighborhood that has gradually become home to a predominant minority Hmong population. His unflinching expletives and racial comments seem funny because they are so over the top, much like a Don Rickles performance.

Early in the film Kowalski gets caught up in a conflict with a gang that is harassing his neighbor. And in strange twist of events, this supposed racist becomes a savior for the Hmong family. Up to this point, Eastwood is playing the icon exactly according to the American mythic narrative.

We as a nation would just as soon keep to ourselves. We get in wars only when forced. We don’t want to be a part of some big global cooperative. We’d prefer to go it alone. And yet, we dream that we are really the world’s savior. Whether our mythic values are truly lived or not, Americans consistently reflect variations in our icons.

But then something odd happens. Kowalski is changed by the Hmong family. A Hmong shaman speaks the same words of wisdom that Kowalski’s priest has been trying to teach him. On multiple levels the family enters his life and begins to soften his heart and teach him how to life. Since he knows a lot more about dying.

Spoiler alert: As Walt softens, he can finally enter into relationship with other people including his priest. He is becoming more human. As he begins to live, he offers something Dirty Harry was incapable of offering. He loves. In his love, he is willing to die for the relationship, so that the Hmong family can really be helped instead of a temporary fix through an act of violence and vengeance.

In one act of sacrifice, Walt becomes father to the Hmong boy, judge to the gang, healer to the Hmong family and possibly even a prophet to his own family. Eastwood connects with the American icon but then challenges us to enter into relationship and to learn that sacrifice may open doors that power and violence cannot.

As I dream of what America could be, I am going to keep thinking about Walt Kowalski and the power of modeling the cross, laying down my life on behalf of those I love. And if I follow the rhythm of the gospel, this means loving my enemies as well as my friends.